What I learned from a four-day design sprint with government partners

Gillian Wu

July 22, 2021

Hi there! My name is Gillian, and I am the UX Design Fellow that is part of the 5th cohort working at Code for Canada to improve digital governance. Alongside my teammates Malik Jumani (Product Manager Fellow) and Ian Cappellani (Developer Fellow), we are working with the Canada Energy Regulator (CER) to improve the tools that Canadians use to participate in hearings regarding energy projects regulated by the CER.

To learn more about us, click here.

After consolidating research, I ran a weeklong design sprint workshop with my fellowship team and government partners.

The intention was threefold. The main goal was to gain buy-in and trust from government partners while creating potential solutions for the problem space we were focusing on. I also wanted to introduce new methods of problem-solving and build internal capacity by teaching different digital tools for collaborative work.

I referenced the book, Sprint, to lay out the workshop plan but had to make some modifications to it. I constrained the workshop sessions to one hour per day across four days as my government partners were often busy and had their own projects to work on.

Luckily, my co-fellows and I had already done a lot of research before coming into the workshop, which allowed us to share the information with our partners so we can hit the ground running.

Prep before the workshop

I developed a workshop schedule based on the time constraints. My team created hands-on instructions for using Miro before the start of the workshop so participants can get comfortable with using a new tool. I packaged this in with the schedule, research summary and a high-level journey map.

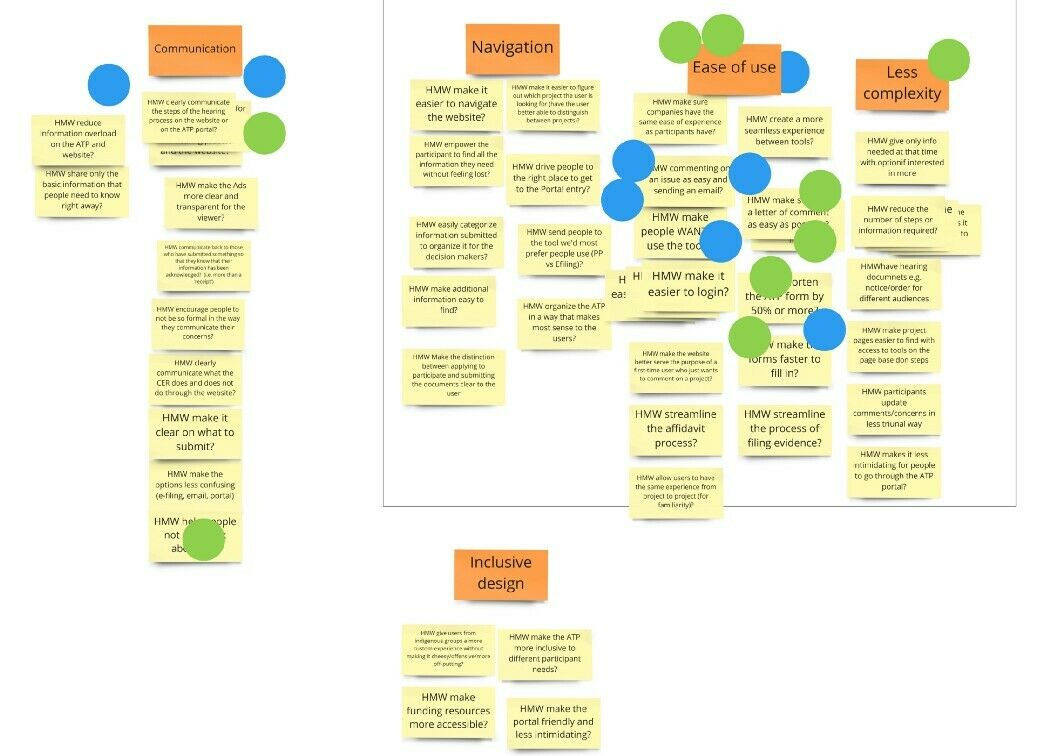

Day 1: Picking a problem and choosing a target

On the first day, the goal was to pick a problem and an area of the participant workflow to target for the sprint.

I had my government partners look through some of the research that was gathered and ideate on potential problem statements. Before we wrapped up, we sorted the information and voted on the area of focus to align on the sprint goals.

We ended up with the main goal of reducing the amount of time it took for people to register in a hearing process by 50%.

As homework, I instructed people to find inspiration from product and services they loved that relates to the work we are doing. I also sent out a video and article on the SCAMPER technique, a method of problem-solving that would help the participants with the activity for the next day.

The SCAMPER technique stands for substituting, combining, adapting, modifying, putting to another use, eliminating or reversing. It helps teams think of different ways to solve problems and create solutions.

After the workshop, I reached out to a pool of user testing participants for when we planned to get feedback.

Day 2: Presenting design inspiration and crazy-8s

On the second day, the workshop participants presented each of their findings and how the elements from other products can potentially be used in the redesign.

Some of the inspiration included looking at existing regulators, banking or fintech apps that deal with legal constraints, and cooking apps that showcase the methodological steps.

Inspiration can come from various sources, so look beyond the products or services that relate to the work you are doing.

Considering how best to reduce the time it takes to register for a hearing process, participants used the research and inspiration to sketch out 8 potential ideas in 8 minutes (this is known as crazy-8s). Sketches can come in many different forms such as stick figures, text and shapes.

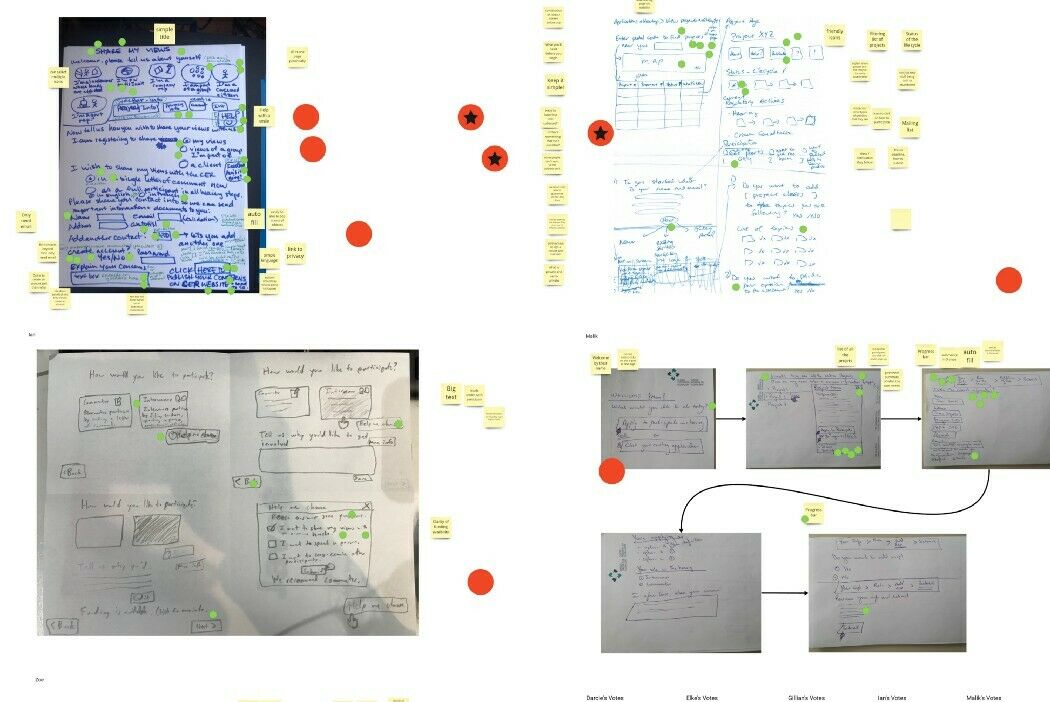

Day 3: Refining the sketches and presenting the concepts

The participants chose their favourite crazy-8 designs. Taking their top selection, I created a refined version of it.

We spent the last 15 minutes going over the design concepts. We did not have time to go through everyone, so this continued onto day four.

Day 4: Presenting concepts and voting on the sketches

On the final day, we went over the sketches of those who did not have a chance to present. Everyone was given 10 dots to vote on their favourite elements in the array of work.

We also had one person be the final decision maker on the design direction we go with. Typically, the main decider is the major stakeholder of the project (such as a VP). If they cannot join, pick someone that understands the perspective of this stakeholder and get sign-off from them. It is important to have someone as the main decider when participants in the workshop cannot agree on the design direction.

Beyond the workshop

My team and I took the final agreed-upon sketches and mapped them onto a storyboard. I spent the next two days turning it into low-fidelity wireframes.

The result of our four-day design sprint?

We were able to create a working prototype to test with various users.

I scheduled the user testing sessions for the Friday after the workshop. This gave me enough buffer time to complete the designs, while not being bogged down by constraints.

When we tested, my co-fellows acted as note-takers during the session. They also helped map out the insights after the sessions were completed.

Learnings

What worked

I saw my government partners go from skeptical to buying-in to the design process. Many of the ideas they had used were incorporated into the final designs. This process helped them get comfortable with organic ways of problem-solving and led them to become a major voice for the users.

The modified sprint also allowed us to rapidly iterate and test new design concepts within two weeks.

Dot voting was a great way to include different stakeholders into the conversation without the need for long-form discussions.

What didn’t work

While this type of sprint makes everyone feel involved, it should not be used in every project. If you are working within a startup, have a lack of time, or want to innovate, this might be a good method to try. However, the 1-hour workshop sessions don’t provide enough time for deep thinking and system considerations.

It is not a good replacement for a proper design sprint. Our team had the chance to do research over 1–2 months. Without it, we would not have fully understood the breadth or depth of the problem space.

In addition, we ran into issues later on because the system was not fully fleshed out with our government team. We were time-constrained within this sprint. Ideally, we would have taken more time to understand how the redesign impacts the existing processes and systems in the organization.

Unlike startups that tend to be nimbler, changing government processes take time.

Stakeholders are busy, which means it is difficult to get their time. Sometimes, there might be a fear of change, risk aversion or the mindset that ‘this is the way we have always done it’.

In government, there are checks and balances in place. If you move too quickly and break things, it can potentially have negative impacts on many people.

Our team worked around the barriers by coming up with a plan and presenting different options to the decision-makers before we had our meeting. Sometimes, we cannot wait around, which means we need to take thoughtful risks and work in parallel to get things delivered on time.

Other times, it is important to include longer-form discussions over silent dot voting when you need to flesh out complicated processes.

Finally, sometimes our government partners could make all the workshops because of conflicting projects they were working on. This has some impacts on the rest of the sessions as it is woven into a tight timeline.

At the end of the day, it is important to be intentional with the methods you use. The methods in this sprint is simply one tool out of the many out there. Overall, it was a success for our team because it built digital capacity, created buy-in from our government partners and helped us deliver a quick prototype. However, this method was time-consuming for our government partners, so we did not continue to use this in later iterations.

You're here to help residents, and we're here to help you. Interested in how to bring digital tools and skills into your department? No matter where you are on your digital government journey, learn more about how Code for Canada can support your work.

End of articles list