Meeting Canada’s newest aviators

Andee Pittman

March 11, 2019

Do you remember when digital cameras were all the rage? The availability and affordability of a new technology combined to make owning a digital camera an option for everyday consumers. Today, drones are doing for aviation what digital sensors did for photography; simply replace Canonsand Nikons with DJI Sparks and Mavics. Similar to how digital cameras created a new user group in their field, drones have created a new user group in aviation. And just like how early adopters of DSLRs may not have considered themselves professional photographers, drone operators don’t consider themselves to be pilots.

But unlike photography, this disconnect could have much bigger consequences.

From “hobbyists” to “pilots”

With access to airspace comes great responsibility. Transport Canada’s job is to protect the millions of global citizens that pass through our skies every day. With drones suddenly appearing in those skies in greater numbers, Transport Canada revised their regulations, and a new set of rules governing drone use will come into effect on June 1, 2019.

The goal of these new regulations is to move drone operators from “hobbyists” to “pilots.” As a class of users, pilots are required to follow regulations to ensure safety. The term “pilot” connotes responsibility. If you’re like me, you want the person flying the plane to know everything about their job, and to be able to prove it with a license.

“We’re here to learn how we can shift recreational drone operators’ perspectives and make it easy for them to follow the rules.”

That said, Transport Canada predicts that it may be challenging for drone hobbyists to adopt a pilot’s mindset. And that’s why the Digital Drone Collective is here!

User-centred regulation and service delivery are rolling-out across Transport Canada, and the Ministry’s partnership with Code for Canada creates an opportunity to put that mandate into practice. We’re here to learn how we can shift recreational drone operators’ perspectives and make it easy for them to follow the rules.

To do that, we first need to understand how they currently view themselves and how — if at all — they’re engaging with regulation. That’s where our user research journey begins.

Meeting with Canada’s newest aviators

We interviewed a range of recreational drone operators, from a professional photographer to a single mother. We spoke with drone operators who were unaware of regulations (fortunately there was only one!) as well as drone users with a background in aviation. Our hypothesis is that what the latter struggle with is likely to be a larger obstacle for the former.

We found participants through personal networks, and Respondent.io, a digital recruitment platform. We tried to recruit on Reddit, but drone subreddit moderators wouldn’t approve our posts. Instead, we collected insights through posting questions as fellow drone hobbyists. We asked them about who they are, why they fly, and about their motivations. We also focused on their processes in flying: what information sources they consult, what questions they ask before flying, where they do and don’t fly, etc. We were particularly interested in understanding how safe they felt their personal processes were.

Here’s what we learned…

1. Their drones are digital cameras. With wings.

Many users see themselves as photographers, not pilots.

6/10 users told us they use their drone for aerial photography. Like the digital photographer I mentioned before, these users are motivated by the low cost of drone technology. They see aerial photography as a way to capture unique and breathtaking images. And they measure success by the quality of their photos, or in some cases, their interactions those photos garner on social media.

“Being able to record. You can see a lot more than you would be able to. It gives you views like you’re in a helicopter. It’s the ability to see the landscape that you can’t otherwise from being on the ground.”

— Drone user

These participants also have no prior aviation experience. That is, unless, you count the one person who had flown model helicopters.

2. Once you buy a drone, you’re on your own.

Users found it challenging to discover reliable information about how to operate drones safely. They named retailers, manufacturers and government websites as potential sources of information.

Participants told us that there was no reliable, single source of information to help them learn how to be lawful drone operators. Many felt that it was the responsibility of retailers to raise awareness of safety and regulations.

“A lot of people assume it’s like flying a remote control helicopter, that’s their mentality going into it, so they underestimate. That should be down to the consumer level, getting warnings, or information on how to learn how to fly. It’s not touched upon when you’re buying it, you just tear the package open and you go.”

— Drone user

To learn more about the retail experience, and to understand what consumers’ entry into the world of drones is like, we went to a store and bought a drone during our first design sprint. The sales associates weren’t able to answer questions about drone regulations or rules, although one employee did try to Google it for us. The store had placed a URL on the drone display, suggesting we could visit the page and learn more about drone safety. However, the link took us to a listing page of drones on their e-commerce website. There was no mention of regulations or safety.

To our surprise, participants also felt manufacturers were missing learning materials. DJI had “no-fly zones” built into their application, but users found they weren’t always accurate. One user was fined for flying in airspace that wasn’t listed in the app.

This echoed our own experience. When we purchased a drone for research, we decided on the DJI Ryze Tello. It was the most affordable drone that met our needs. We discovered that the manual did not have the most up-to-date link for the tutorial videos. They didn’t describe emergency procedures or include troubleshooting information.

Without support from the retailers and manufacturers, many users turned to YouTube and online forums. Their process included cross-referencing several sources to learn how their drone performs. This was time-consuming, and they still felt uncertain about their knowledge.

“It’s kind of like you’re doing your history homework and trying to get information from as many resources as possible.”

— Drone user

Despite having the best chance of knowing how to comply, users with aviation backgrounds also struggled. One person told us that they had spent a year figuring out their “operating procedures.” They said it was challenging to find the information they were looking for because it was distributed across a number of different government websites.

On the positive side, users expressed a high degree of trust in Transport Canada, and said they would rely on the Ministry as their single source of information on how to fly drones responsibly.

3. “How do I do what you want me to do?”

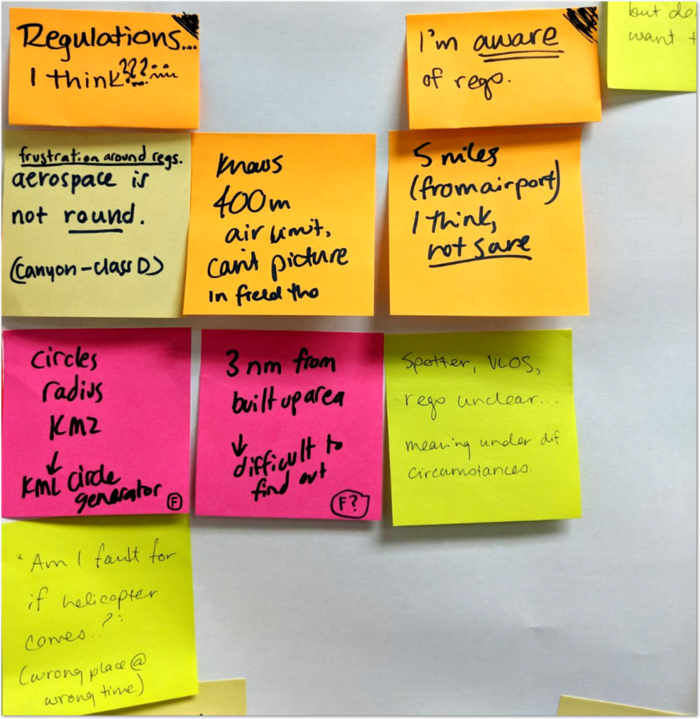

Both participants with aviation backgrounds and those without had challenges putting regulation into action.

Users without aviation backgrounds were generally not flying in compliance with regulations, relying instead on “common sense.” Some had informed their personal processes by consulting regulations, yet most couldn’t recite accurate distance restrictions around airports or other specific rules. Notably, many felt the regulations didn’t apply to them as hobbyists.

“I think it’s 5 miles from an airport? I’m not sure on that.”

“I think if you wanted to fly in airspace, you’d need a flight plan, detailing where you’re flying when. But I don’t know how I would do that”

— Drone users

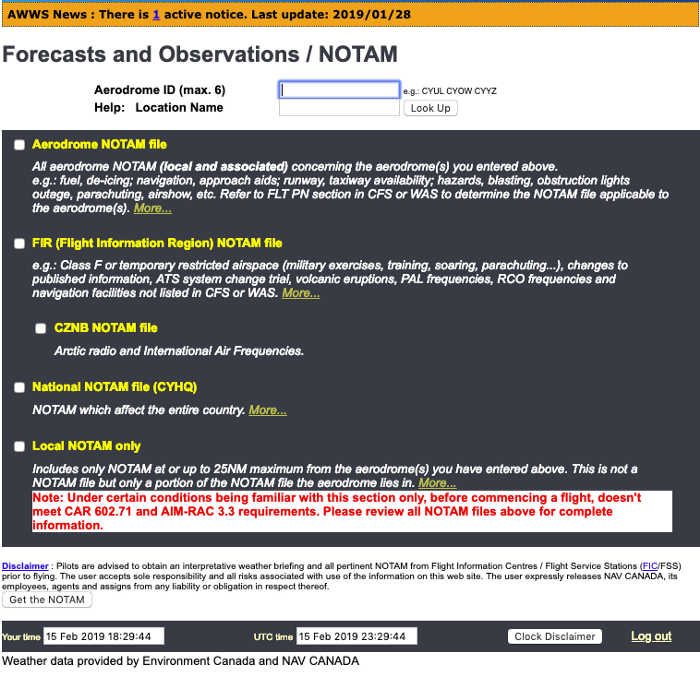

Participants with aviation backgrounds had difficulty using existing government tools like the NRC Where to Fly tool. They also expressed challenges in checking Notices to Airmen (NOTAMs), official communications that alert pilots of potential hazards at a given location or along a given flight route. They felt that the current website is designed for traditional aviation. When it comes to small drone flight paths, they felt tool is hard to use.

Again, we predict that if more experienced users struggle with these tools, hobbyists are likely to find it even more challenging.

Next steps

If those with aviation backgrounds find it challenging to follow current regulations, how are those without going to succeed? How can we help them do the responsible “pilot” things that will keep everyone safe? How can we leverage technology to support this broad and diverse group of Canadians?

We have begun to get a sense of the behaviours, beliefs and needs of recreational drone pilots. They are not quite pilots, yet. They are photography and technology enthusiasts, unlikely to have prior aviation knowledge. We learned users struggle with a lack of information, and don’t find support in the places they would expect: from retailers, manufacturers, or the government.

With more regulations, requirements and expectations of this user group landing soon, our next step is to think about where support should go first. Where in the journey will new digital tools be most impactful? And wherever and however we intervene, we will need to design for our users as they are, not as pilots, but as hobbyists and purchasers of winged cameras.

To figure this out, we will synthesize all our research and evaluate challenges on their impact on achieving safety. We’ll also consider the interoperability of the opportunity. Will solving this challenge support the users with other challenges in their journey?

Once we know what problem we’re going to solve, we will craft our problem statement. Then the real fun begins: how do we solve this?

Learn more

Read more of our findings in the Digital Drone Collective’s newsletter in the upcoming months. If you haven’t yet, subscribe here. Do you want to be involved in future research? Let us know here.

And before we go, we want to thank all the wonderful people we’ve spoken to so far. If stories are the currency of humanity, we’re getting richer by the day. Sharing their names would break anonymity, but these humans deserve big high fives. Hopefully, they’re reading this, and hear our appreciation.

End of articles list