How can we offer digital services without understanding what people value?

Andrea Hill

January 29, 2020

Code for Canada fellow Andrea Hill explores some of the tensions and differences between user research and public opinion research in government.

Joining the public service as a Code for Canada fellow after 15 years in the private sector has been a very eye-opening experience. I knew there would be some cultural differences, but they’ve been in areas I never would have expected!

One is in the area of research. User research has been at the core of my entire career, starting as a prototyper in the private sector back in 2003 (!) I’ve conducted hundreds of user interviews, but I knew I had more to learn when I had this doozy of an ethics guide shared with me a few days into my new gig.

Universally, user researchers steer clear of opinion questions. I was thrilled very early on to hear the drumbeat of “FACTS AND BEHAVIOURS, NO OPINIONS”.

What’s surprised me, though, is the definition of what constitutes an opinion, and why it’s so important UX researchers with the government of Canada steer clear of opinion-based questions!

Public Opinion Research

According to the Treasury Board, public opinion research is:

The planned, one-way systematic collection, by or for the Government of Canada, of opinion-based information of any target audience using quantitative or qualitative methods and techniques such as surveys or focus groups. Public opinion research provides insight and supports decision making. The process used for gathering information usually assumes an expectation and guarantee of anonymity for respondents. Public opinion research includes information collected from the public, including private individuals and representatives of businesses or other entities. It involves activities such as the design and testing of collection methods and instruments, data collection, data entry, data coding, and primary data analysis.

Usability research and ‘behavioural or factual research’ are explicitly called out as not generally considered public opinion research. When public opinion research is going to be undertaken, public servants need to refer to the Mandatory Procedures for Public Opinion Research (Appendix C of the Directive on the Management of Communications), and there’s quite a lengthy process to follow.

So, it’s clear why a researcher would want to try to steer clear from public opinion research. The question then becomes, what are they giving up in doing so?

Can you ask attitudinal questions without it being classified as ‘public opinion research’?

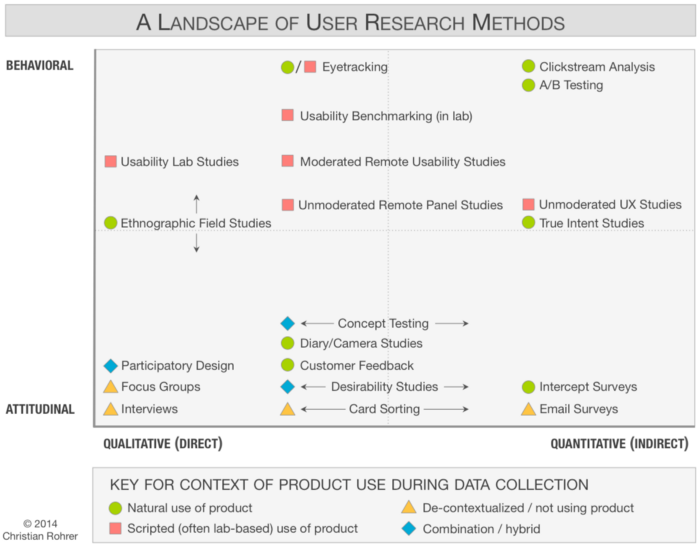

There are a wide variety of user research methods. In addition to the qualitative-quantitative spectrum, there’s also a range between behavioural and attitudinal inquiry. We know that usability and behavioural research is NOT considered POR, but does that mean that anything else IS considered public opinion?

Here’s the thing.. we can measure behaviour only once we have something to measure. We have to already be in the solution space. At that point, we’re doing evaluation.

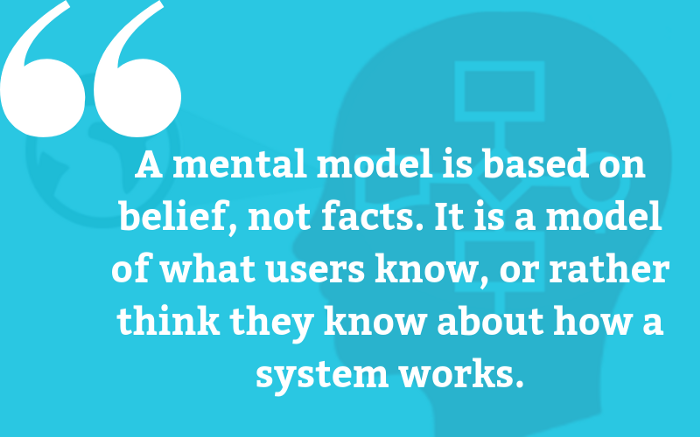

As a designer, I need to be operating a few steps before that. I want insights into user needs to design the right thing. I don’t want to simply guess, and then measure whether it’s usable. I want to be conducting problem space research. I want to delve into my users’ mental models, so I can design a solution that fits into their understanding of the world.

If we focus only on what users do, and shy away from the why, we’re severely limiting our ability to serve them. I’d go so far as to say we’re actually preventing ourselves from developing empathy. We can’t call ourselves human-centred designers if we refuse to acknowledge the human experiences that drive behaviour.

Why are attitudinal questions to be avoided?

Where does this aversion come from? Is it externally or internally imposed?

- Are they furthering a political agenda?

- Are they “bad” or “misleading” from a UX research perspective?

I’ve heard some suggestions of where this may stem from, but nothing official. (Dare I say, I’ve heard opinions, but maybe not facts?). If there’s an official explanation anywhere, I’d appreciate the reference!

At some point of trying to understand why things are the way they are, I had to ask myself if it really mattered anyway.

Do user preferences even matter when you’re operating as a monopoly?

In order to win in a free market, a company needs to offer a product or service that meets user needs ‘better’ than alternatives. According to Jobs to be Done, users will ‘hire’ the products and services that will help them get their jobs done better, faster or cheaper. So how do we find out which alternatives exist, and what users are choosing?

Back to our two research approaches: we can observe them (behavioural), or we can ask them (attitudinal).

Except — we’re talking about social services here. We can’t observe users’ choices, because they don’t have one. They have the single service that we offer.

Well, you may be saying, we can observe them using our own service. We can see how they use the service we already have, and go from there.

Yes… but…when you’re being innovative and coming up with something new, there’s nothing to measure! There may not be any ‘facts’ related to how something is done currently, because it may not yet be possible! Not to mention, you’d have to already be well down in the solution space once you get to the point of measuring the usability of a specific proposed solution.

So, it’s possible that as a monopolistic supplier, we actually don’t have to worry about providing a solution that meets users expectations. Because they don’t have a choice.

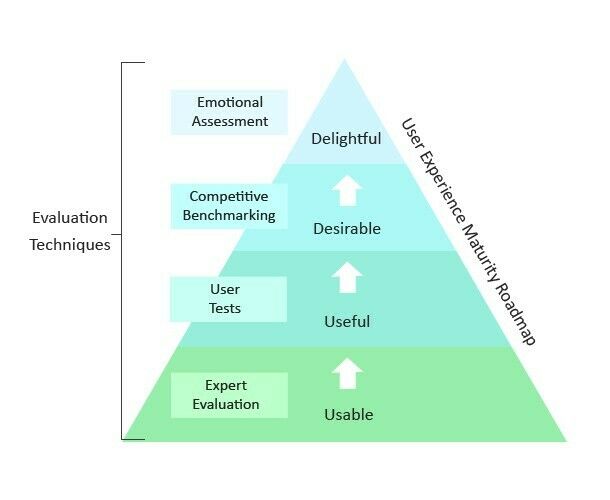

We could get away with offering the bare minimum of service for our users, “usable”, and they would use it, because they lack choice.

I don’t know about you, but I want to do better. I believe our users — our citizens and residents — deserve better.

So let’s go above usable, and aspire to offering something useful, desirable, any perhaps even delightful (!). If we aspire to offer a solution that meets our users’ expectations, we have to do things a different way. First off, we need to figure out what those expectations are. But, is an expectation a fact? Can it be observed?

As it stands now, the path of least resistance is to steer clear of the murky waters of POR and just measure whether something’s usable. Can I get my work done through this tedious process? Yes. Is it a mind-numbing, painful process? Maybe — but users don’t have choices.

By calling out usability testing as a way to engage with users through the product development process, we draw attention away from other types of research. Usability research is “safe”. It’s measurable. When you measure users’ abilities to perform tasks, you can report back a nice clean result.

But are we ignoring the “why” behind the “what”? For many designers, that “why” is critical. The “why” helps us better understand the underlying job the user is trying to get done and what’s important for them to feel successful and confident. If someone can complete a task but the system or process is frustrating and leaves them disappointed, confused or angry, we haven’t delivered on our promise to design a good experience for them.

When we’re designing services, we need to put the people we’re designing for before our own processes and policies.

How does research dovetail with inclusive design?

Inclusive design is a bit of a buzzword now in 2019. Inclusive design can be defined as “design that considers the full range of human diversity with respect to ability, language, culture, gender, age and other forms of human difference.”

These 6 Principles for Inclusive Design are fantastic:

- Seek out points of exclusion

- Identify situational challenges

- Recognize personal biases

- Offer different ways to engage

- Provide equivalent experiences

- Extend the solution to everyone

When we choose to focus only on ‘facts and behaviours’, we ignore the human experience. Yes, I can park in the back of a dimly lit parking garage, cross railway tracks and walk several blocks to my hotel in the middle of the night, but I’d prefer not to.

Is my experience invalid?

What if I tell you I’m a petite woman, or that I’m in a wheelchair. Does one or the other make my preference (or need) more reasonable?

Do I need to justify my preference by giving you my gender and stature? Or does what I prefer not matter — and does that make me feel like I don’t matter?

We get into a slippery slope when we start trying to differentiate between preferences and needs.

Who are we serving when we put the burden on individuals to prove they need something (as a fact — provide a health certificate, etc)? Is it not more respectful and humane to recognize that our human experience is much more than what can be demonstrated, observed and measured?

The sixth principle of inclusive design is to extend the solution to everyone. If we truly believe we are engaging in inclusive design, we need to release ourselves from this tight grasp on facts. If it’s a fact that anyone cannot stay in this hotel, and we have to offer an alternative, then we need to open it up to everyone. At that moment, does it matter whether we designed for the person who couldn’t, or the person who preferred not to?

Could we have just started with understanding and empathizing with the concerns, and fostering some goodwill, rather than only offering a solution begrudgingly because someone proved they needed it?

Since starting my fellowship, I’ve been counseled numerous times that “this isn’t the private sector”. Constraints foster creativity, and I relish the challenge of figuring out how we can deliver delightful experiences to the public while respecting data protection and other relevant policies and procedures. But this can’t be an excuse to offer lackluster experiences at scale simply because “that’s the way we’ve always done it.”

We need to put the people we’re designing for before our own processes and policies.

This post has sat in my ‘drafts’ for months, and I found myself sharing some of thoughts at a meetup last night. I’ve been reflecting on my time within the public sector, and I think this has been one of the most jarring aspects. I’m sharing this in the hope of starting a conversation and hopefully gaining an understanding and acceptance for this train of thought. 🤷♀️

Further Reading

- Defining public opinion research (2016–11–08)

https://www.canada.ca/en/treasury-board-secretariat/services/government-communications/public-opinion-research-government.html - Mandatory Procedures for Public Opinion Research (2016–05–11)

https://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/pol/doc-eng.aspx?id=30682#appC - Standards for the Conduct of Government of Canada Public Opinion Research — Qualitative Research (2019–04–02)

https://www.tpsgc-pwgsc.gc.ca/rop-por/rechqual-qualres-eng.html - Scaling Design Research in the Government of Canada (2019–06–26)

https://digital.canada.ca/2019/06/26/scaling-design-research-in-the-government-of-canada - A guide to interviewing from the Canadian Digital Service

https://digital.canada.ca/tools-and-resources/guide-interviewing/ - Usability Testing is not Public Opinion Research (2014–07–31)

https://www.akendi.com/blog/usability-testing-is-not-public-opinion-research/

End of articles list